RACHEL BOTSMAN:

“The issue of trust does not lie in the technology, it lies in the culture.”

The disruption – both positive and negative – that we are experiencing from new technologies, comes from the shift in trust.

Rachel Botsman

Rachel Botsman is a leading expert on trust in the modern world. As the Trust Fellow at Oxford University’s Saïd Business School, she aims to challenge and change the way people think about trust and related topics such as power, influence, truth and beliefs.

In the world we were used to, trusting was easy. Institutions, banks, newspapers – we knew we could rely on them for everything: they protected our identities, they guaranteed payments, they gave us secure bricks to build our world of beliefs.

Then digital technologies changed everything: the way we live, how we work and consume, how we do business. New opportunities escalated, and traditional hierarchical institutions started breaking apart – bringing with it a breakdown of trust. Google, Facebook, Airbnb, Uber – these disruptive platforms, networks and technologies have changed the face of their respective industries, and so too have they have changed our relationship with trust. Now the pandemic has accelerated our transformation into the digital world. Who can we really trust now?

We feel lost, and we definitely feel that we have to build back some safety nets. We might be able to maintain some forms of shelter from the past, but we also need to find novel paths for trust in the digital world. Can trusted digital identities help? And regulation?

We talked with Rachel Botsman, world-renowned expert and Trust Fellow at Oxford University’s Saïd Business School, to try and get to the heart of the whole issue. We had been looking at the technologies, but as Rachel shows us, trust is a matter of culture and innovation. Read how we as individuals, together with governments and companies, can help in changing the culture of trust around our new technologies. For the benefit of everyone.

We live in the post-truth era. We struggle, in our online lives, to understand what is real and what is fake. Most importantly, we no longer know what information is trustworthy – from politics, to health, to finance. Are we truly living in a world without trust?

What we tend to hear is that trust is in a state of decline. We don’t trust institutions, we don’t trust the media, we don’t trust politicians. This has never added up to me: is trust really in such state of free fall? It’s peculiar because before the pandemic you would still see people finding a date on Tinder, getting into someone’s car with Uber, sharing their home on Airbnb.

These are all phenomenal forms of trust. We are not losing trust; what has happened, I think, is that who we trust has changed. It’s much more helpful to think of trust as energy: it doesn’t get destroyed, it changes form.

If trust has not vanished, who are we actually trusting right now?

Historically, trust has existed in three forms – I’m speaking very generally here – the first one being local trust, the second institutional trust. Now we are in the age of what I call distributed trust.

When people used to live in tribes, villages or small communities, trust was largely interpersonal: it was based on personal reputation and proximity. Then urbanisation and trade came in, we needed to interact with people not in our proximity, we needed to trust them. The local trust mechanisms did not work anymore.

We may not like them today, but we invented institutions, contracts, insurances and so on. These things were amazing, they allowed us to trade, interact and grow in ways that would not have been possible otherwise. Institutional trust took us all the way through the industrial revolution. The important thing is that technology at this point was largely only about enhancing human capabilities.

Today, technology is something else: we have automation, artificial intelligence, cryptocurrencies, new payment systems, digital identity… Today, technology is inherently taking the trust – a trust that was very centralised in institutions: hierarchical and often controlled – and distributing it to networks and platforms.

Look around you and you will see this shift everywhere, with information being the easiest case. The age of the big media companies and newspapers controlling the information we had access to was the age of institutional trust; social media is a distributed trust example.

“We are not losing trust; what has happened, I think, is that who we trust has changed. It’s much more helpful to think of trust as energy: it doesn’t get destroyed, it changes form.”

Further reading

Find out how technology is revolutionising the nature of trust and other issues about our digitally-driven future in Rachel Botsman’s books Who Can You Trust? (2017) and What’s Mine is Yours (2010).

Learn more

How do the new forms of distributed trust affect our lives?

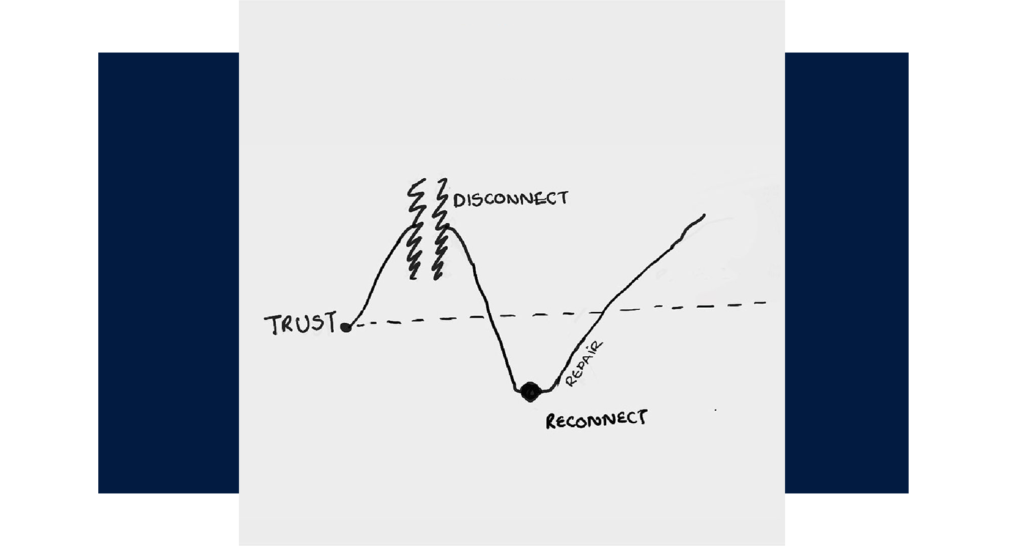

A lot of issues that we are facing, the disruption – both positive and negative – that we are experiencing comes from this shift in trust. It is painful because in so many areas of our lives we have to reinvent the social safety nets that the institutions provided for a very long period in history. And things are constantly changing. Even in distributed systems, you still need a centre: a company, an institution, a person who is accountable. This is one of the biggest transformations we have seen over the last five years.

The idealistic version of the distributed trust – that trust exists between people, so they can resolve things – does not work. In particular, it doesn’t work when something goes wrong with safety, security or data privacy.

“I think people have become more aware of the digital representation of themselves, more than in traditional media and more than in any other time in history.“

Some mechanisms that worked in institutional trust to mitigate the risk (e.g. insurance, regulation) are still really important in the digital world. And we must also find new mechanisms. One is a trustworthy digital identity: how do I prove in the digital world who I am in the real world?

Has the pandemic changed the way people think about digital identity?

In the pandemic, most of our identity has become digitalised: the way we interact is almost exclusively through digital means. I think people have become more aware of the digital representation of themselves, more than in traditional media and more than in any other time in history.

The second obvious impact of the pandemic is the digitalisation of services that would have otherwise likely taken decades of innovation to reach this point. Online commerce, digital learning, virtual health, payments. All these things had their own physicality; now they are tied with our digital identity.

And it happened very quickly. In terms of trust, we still have to somehow adapt to all these changes. Can I tell you a funny story about this?

“There is still a disconnect between professionals and technologies they have to work with.”

Are you into trust issues?

Rachel has been sharing her thoughtful insights on trust in her podcast: Trust Issues, her newsletter and in articles published in a number of respected media.

We can’t wait to hear it…

I was sick the other day. I have a smart watch, and I sent my heart rate to my doctor. The first thing he said was,“Something is wrong with your watch”.

I was actually sick, but my doctor didn’t trust the technology.

There is still a disconnect between professionals and the technologies they have to work with; technologies that could actually tell you a lot about the identity of a person. I think it is slightly frightening, and we all are perceiving this, but at the same time it is phenomenal in terms of the trust leaps that people are making.

Do you have any other examples how the pandemic has changed – for good or bad – the landscape of trust in the digital world? Which of these “disruptions” are likely to stay in the next 10-15 years?

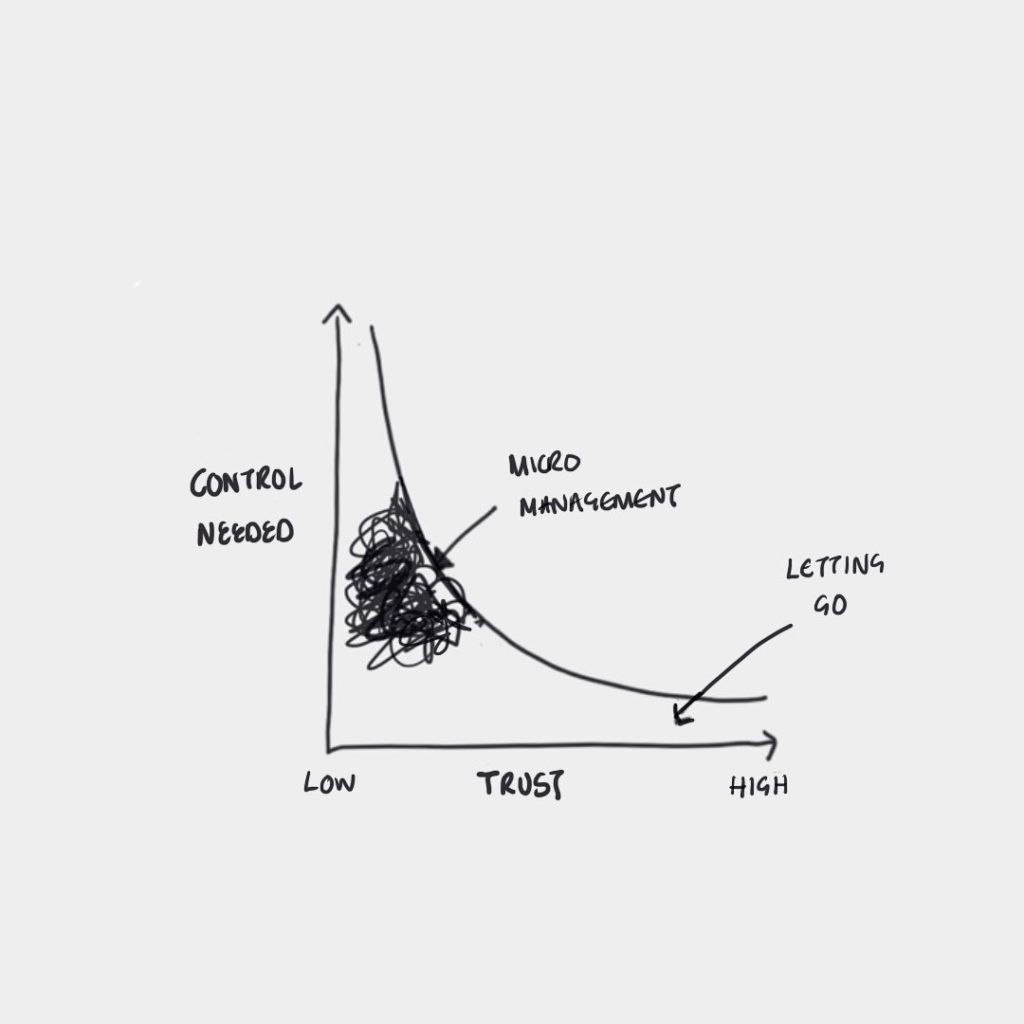

Companies have been forced to change. Some of them trust their employees more now: managers have started to rely more on the members of their team, and are abandoning micromanagement. Other companies have begun to surveil their employees’ work, recording from the camera. For sure, in both cases the pandemic will transform the dynamics of those teams permanently.

“I think visually. Images, then words.”

See more Rachel’s drawings – follow her on Instagram @rachelbotsman

Retail and commerce have also probably changed forever. Older generations have now become used to online shopping: my mum did not previously trust e-commerce and now she is buying everything on the internet. There is also an interesting shift towards the value of local – we’re buying local food, we want to support local bars and restaurants. Companies are adapting and I think they will continue in this path of combining local and digital.

We have seen another huge trust shift towards virtual health. Recent research has described how patients are more honest and open about some problems, such as mental health, when they relate to a doctor through a computer. There is a real change in the power dynamics between patient and doctor when you sit in the comfort and security of your home.

I hope, in fifteen years, we will get to a point where you pay a health subscription, you send basic medical data through a smartwatch, and one day you receive a call from your doctor saying, “There’s something wrong with your blood pressure, please come and see me.” Basically, the opposite of the slightly regrettable story with my doctor.

Medicine will be far more preventive. This would be a major change – not only in terms of digital integration, but also in terms of trust leaps that people are ready to take.

Technology has shaped our life during the pandemic. And it appears to be the strongest force that has disrupted our traditional values of trust. Yet what we tend to hear from society is very mixed messages about technology, a sort of love and hate attitude….

Virtual homeschooling, virtual working, telehealth: during the pandemic we have learnt to trust all this. For all the talk of a lack of trust in technology, what I see in my research is that we are still placing great confidence in technologies.

I was reading a paper this morning that has shown that when it comes to weight advice, we trust more in the recommendations of an algorithm than those of a human. Interesting, isn’t it? It is fascinating to me what technology we choose to adopt, and what we choose to reject.

In 2018, Facebook launched Portal. It was an amazing product, and they expected to enter the market of home devices. Well – it was complete flop; people said that they did not trust their use of data. So people would still use their social network, but they wouldn’t let them into their home. That is really the power of trust, right?

How can a tech company actively build trust in the digital space?

The issue of trust does not lie in the technology, it lies in the culture. Tech companies should create the right cultures around the technology, and continuously ask themselves whether their product or service deserves someone’s trust.

Facebook can change algorithms, they can have more fact checkers, but fundamentally people do not believe in their privacy around data and they do not believe in their business model.

Let’s look at a completely different sector: the insurance industry. This is a low trust industry because people have very little visibility and control in the policies. If a company wants to provide a new digital service in this area, they should do everything they can – from customer service, to design, to accountability – to build a change in someone’s relationship to insurance. Companies like Lemonade, for instance, are taking this path. Building trust comes from a place of innovation and culture, not from the technologies themselves.

“Tech companies should create the right cultures around the technology and continuously ask themselves whether their product or service deserves someone’s trust.”

“We’ve stopped trusting institutions and started trusting strangers.”

Should governments and politics play any role?

Regulation plays a critical role, and we should not forget that. Regulation is a great mechanism of risk reduction: policies should reduce the likelihood and severity of the risk of something bad happening.

Regulation should also provide backstop: this is where I think it has been incredibly weak until now. If something bad does happen, the company is responsible. The action of governments should set a layer of protection around customers as online services are emerging, without suffocating them.

The last thing, and probably the most important one: we – citizens, customers – we all play a role.

What can we, as individuals, do to contribute to a more trustful digital realm?

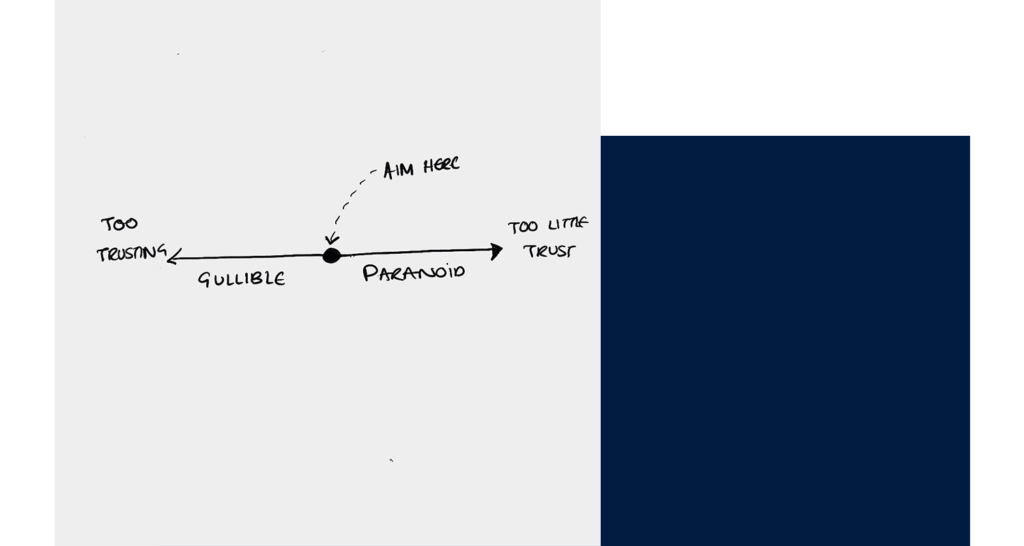

Trust is something you give, and trust is something you earn. We ultimately decide who we give our trust to: which product, which company we allow into our home. Whether we are consuming the daily news, looking for fashion advice or deciding to bring a smart device in our home – we should constantly ask ourselves: am I giving my trust to the right people, the right information, the right product?

“The efficiency and speed of technology makes it very hard to take a pause and think more about the micro-decisions that we’re making.“

And then the flip side of that: think about your own behaviours and actions. It could be anything – in your work, in your daily life – what is it that you are bringing into the digital world, and does it deserve people’s trust?

All this requires a slowing down. It requires becoming more thoughtful about processes that underlie the digital world; it demands thinking about implications. The efficiency and speed of technology makes it very hard to take a pause and think more about the micro-decisions that we’re making. Yet, we should all be more aware that these decisions have an impact. They have an impact on our reputation, on our future identity, on what we are and what we believe. And, also, on the people connected to us.

AUTHOR: Giovanni Blandino

ILLUSTRATION: Matej Mihályi

PHOTOS AND DOODLES: Archive of Rachel Botsman